Phew! That last one was a long read! Since that previous post I’ve had plenty of people ask for a stripped back version of just the basics. Although it would be easier to amend the original post, there is still some good, detailed content there that I want to keep. So instead I’ll make a new one that’s a bit more stripped back and palatable.

Basically it’ll be a version covering the absolute basics of just 3 things:

- Brewing to a style

- Ingredients Selection

- Process considerations

Just so you are aware, this is such a stripped back version of the last post it’s not funny. What follows is the best high level (I’m talking 30,000 feet up in the air) view of these 3 vital aspects of recipe creation. For more detail, drop me a line or look at the first Intro to Recipe Creation post.

So in the name of keeping things brief, lets jump right in!

Brewing To A Style

When you’re at the stage of wanting to make your own recipe, you generally have a grasp of at least one of the following:

- What styles of beer there are.

- Which ones you like.

- A clone recipe found for a particular beer you like.

- What ingredients give that recipe its flavour.

- How different ingredients might alter that.

If you don’t have a grasp of any of these, that’s ok. What I’d do is take your favourite beer and just search for “what style of beer is xyz beer?” Then you can get to grips with that particular beer, read through its style guidelines, preferably while drinking said beer, and try to appreciate each element. Then look for beer recipes within that style to get an idea for what ingredients are the most common and you may have enough of an idea to create your own.

I will say this, expect the chase for the perfect recipe to be an iterative process. There’s plenty of experimentation to be done in all of this and only through experimentation will you really learn the effect of particular ingredients.

Ingredients Selection

With such a massive variety of ingredients available from everywhere in the world, how do you know which to choose? I started in a combination of a few ways:

- Experimentation

- Clone recipes

- Tips and advice

With experimentation it’s common to start with a SMaSH beer, a beer made with a Single Malt and Single Hop. This allows you to hone in on the particular flavour profile of a certain ingredient or see how well a malt/hop play with one another in a beer. From this point you can then start adding more in to expand the character and complexity of the beer. Just be careful as sometimes this kind of method can lead to what’s affectionately called a ‘kitchen sink beer’ where you end up throwing so much in there in the name of complexity that it just becomes muddled and not that great.

What I did when starting to look at ingredient combinations is start back on my last point and think “What do I want to create? Where in the world is that from? What ingredients are typically common in beers from that region?” When I start from that point its quite rare that you get something that doesn’t work, even if it’s not what you originally intended.

Another solid way to go is looking at various clone recipes. Some breweries are kind enough to release their recipes on a regular basis, looking at you Black Hops you wonderful people! Some you might get if you ask nicely enough and some you might just find online from people winging it and getting something that tastes damn close. These have some merit because it gives you an idea for ingredient combinations and flavour profiles that work together really well. They often give me ideas of things I had never thought of that I can bring forward into an idea of my own.

The other thing to do is constantly ask for advice or feedback on a recipe. There’s PLENTY of online resources, forums, subreddits, Facebook groups to post a recipe and get some great feedback! Sure some people may respond with something unhelpful but the vast majority of responses will be greatly helpful I’m sure of it. If all else fails you can always drop me a line by email, or by my Facebook or Reddit profiles and I’d be happy to help you out.

Process Considerations

Ok so once you know what beer you want to brew and the ingredients you want to use to brew it you only have one thing left.

How am I actually going to brew it?

With what you now know about looking at other recipes and getting advice from fellow brewers on your ingredients selection it should be easy to also find a bit of information on things like Mash temperature, pH, boil times for hops, hop stand/whirlpool times, fermentation times and temperatures and packaging tips.

With that said, a brief dive into some of it isn’t going to hurt.

Mash Temperature/pH

A mash is a chemical reaction, it uses enzymes in the grain to convert starch to sugars. The most important ones are Alpha and Beta Amylase, they chop up the long chain starches into smaller pieces that are able to be fermented, the smallest being Beta Amylase.

As with any chemical reaction, it can only happen when certain conditions are met and happens most effectively within a very narrow range of those conditions. The temperature of and environment in which this reaction happens are critical to achieving what you need.

Typically, for a beer that finishes nice and dry but still has a bit of body you’re going to want to aim for around 65˚C (149-150˚F) and a pH of around 5.1-5.6.

Lower temperature will activate more Beta Amylase and you will end up with a very dry beer without much body, higher and it will end up rather sweet with a big body but could end up cloyingly sweet and unpleasant if it’s taken too far.

Lower pH tends to bring out some unpleasant astringent characteristics of the malt and too high tends to just lower the mash efficiency so you’re not getting as much conversion as you need for your beer.

Fortunately there’s a graphic from John Palmer’s book and website “How To Brew” that gives you an easy guide to follow.

Boil, Hop Stand & Whirlpool Times

Simply put, the boiling of hops produces bitterness through the isomerisation (fancy word for rearranging chemical form through heat) of Alpha Acids in the hop flower. How much bitterness is a function of the percentage of Alpha Acids in the hops and the temperature/length of time they are boiled for.

Traditionally, although its current relevancy and efficacy is up for debate, a boil is done for 60 minutes. This provides plenty of time for alpha acids to be isomerised, even in hop varieties that have a low AA content.

If you boil for a shorter time you tend to get more hop aroma and flavour. With the current trend of hop heavy beers like NEIPAs and other kinds of Hazy IPA its common practice, along with large dry hop additions, to use the vast majority of hops at the >10 minutes point in the boil so they retain most of their character.

To further this effect it has also become common practice to perform a hop stand or whirlpool where you add hops only when the boil has finished and in some cases cooled below the point where most isomerisation occurs (roughly 80˚C). They can be left for 10-30 most commonly as longer times do tend to start to introduce some bitterness.

Fermentation Time/Temperature

After the brew day is done, it’s time to add yeast and turn the wort into delicious beer! The biggest consideration for this is what kind of yeast are you using? Lager or Ale.

The reason for this large distinction is that Lager and Ale yeasts are totally different species (Saccharomyces Pastorianus and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae respectively) and have been bred over the years to tend to prefer very different conditions.

Lager yeasts are like a good pulled pork, best done low and slow. Typical temperature ranges and times for a lager fermentation are 8-15˚C and several weeks. Ale yeasts are more akin to cooking scallops, hotter for a short period of time. Typical temperature ranges and times for an ale fermentation are 18-23˚C and are usually done in a week or two.

There are of course several exceptions to these rules, Californian lager yeasts that are originally harvested from the same strain as Anchor brewing’s Steam Ale are technically a lager yeast but fermented at ale temperatures. In the world of Ales you have Saison or farmhouse strains that can be comfortable up to the high 20’s or in the case of Kveik strains, up to a dizzying height of over 36˚C in some cases!

The point is, check out the environment that your yeast is going to be most comfortable in and try your best to provide that. Your yeast will thank you for it and you’ll thank them for the delicious beer they will create.

Packaging Tips

There’s just two aspects to this really, are you Kegging or are you Bottling?

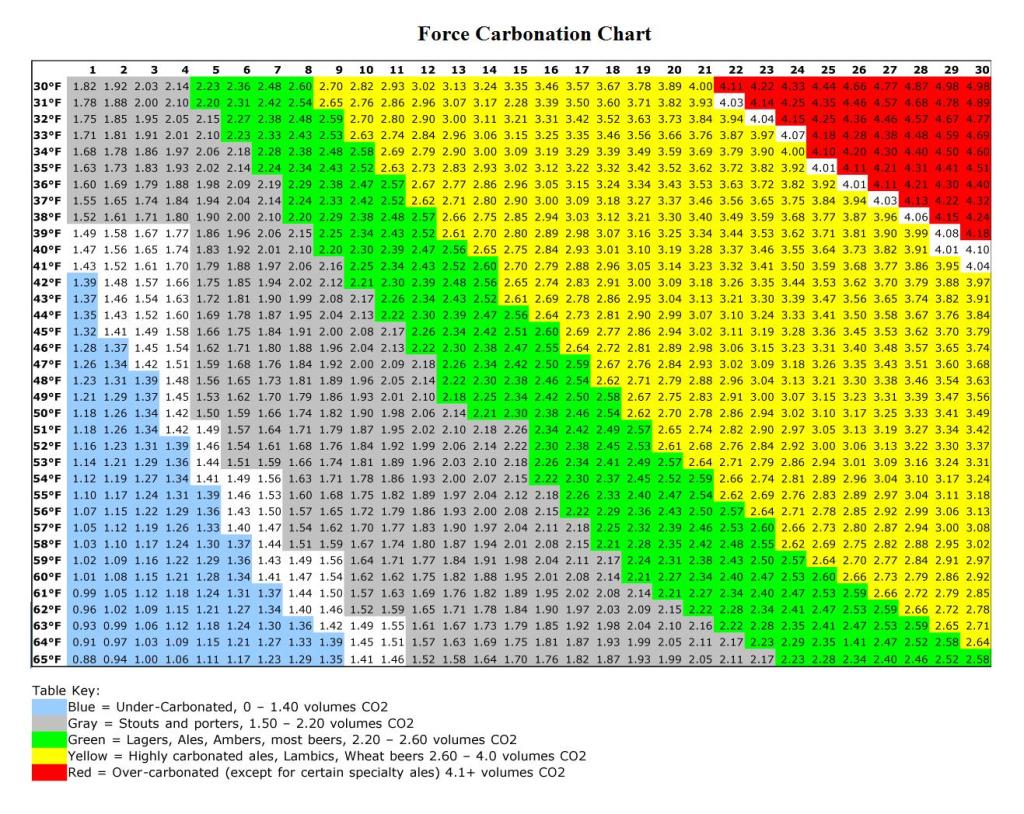

If you’re kegging then you can find several carbonation charts like the one below that will help you find the right pressure to carbonate your beer at for a given temperature. From here, just keep it at that temperature and pressure and enjoy some delicious and consistent beer.

NOTE ON ACTUAL PACKAGING PROCESS:

It’s vital when packaging to try and minimise oxygen pickup in the finished beer. Oxygen can turn a delicious beer into something that is the same thing dialled down to 50%, muting hop flavour and giving the malt profile a stale, papery taste. Imagine a beer that tastes how an old book smells, not great.

That’s done if you’re kegging by doing a closed transfer if possible. This is done by connecting the gas out post back to the airlock of your fermenter and just siting the keg underneath the fermenter to let gravity do its thing. When carbonating a keg you can either do what Brülosophy calls the “set and forget” method, the “crank and shake” or the “burst carbonation” method. Each provides different levels of risk and reward but it’s worth doing a read up on each. I use a modified crank and shake method where I will crank up the pressure to around 40 PSI (270 kPa), give the keg a little shake then turn the pressure of and shake it (while still connected to the regulator) until it moves down to as low as it will go, repeat until its lowest point gets close to your desired serving pressure. I do it this way to reduce the risk of overcarbonation.

If bottling I’d recommend making sure you either purge the top with CO2 or refermenting in the bottle with a small dose of sugar so the remaining yeast consumes the remaining oxygen as part of the process.

That’s all folks! Hopefully that satisfies the previous request for a version of that post that is a little bit more brief. The original post will stay up and I’ll be adding more content soon with the possibility of continuing some previous series’ of posts as well as some interesting collaborations from people on beer styles, reviews and proper tasting and sensory techniques.

Bye for now until next time.

Sean